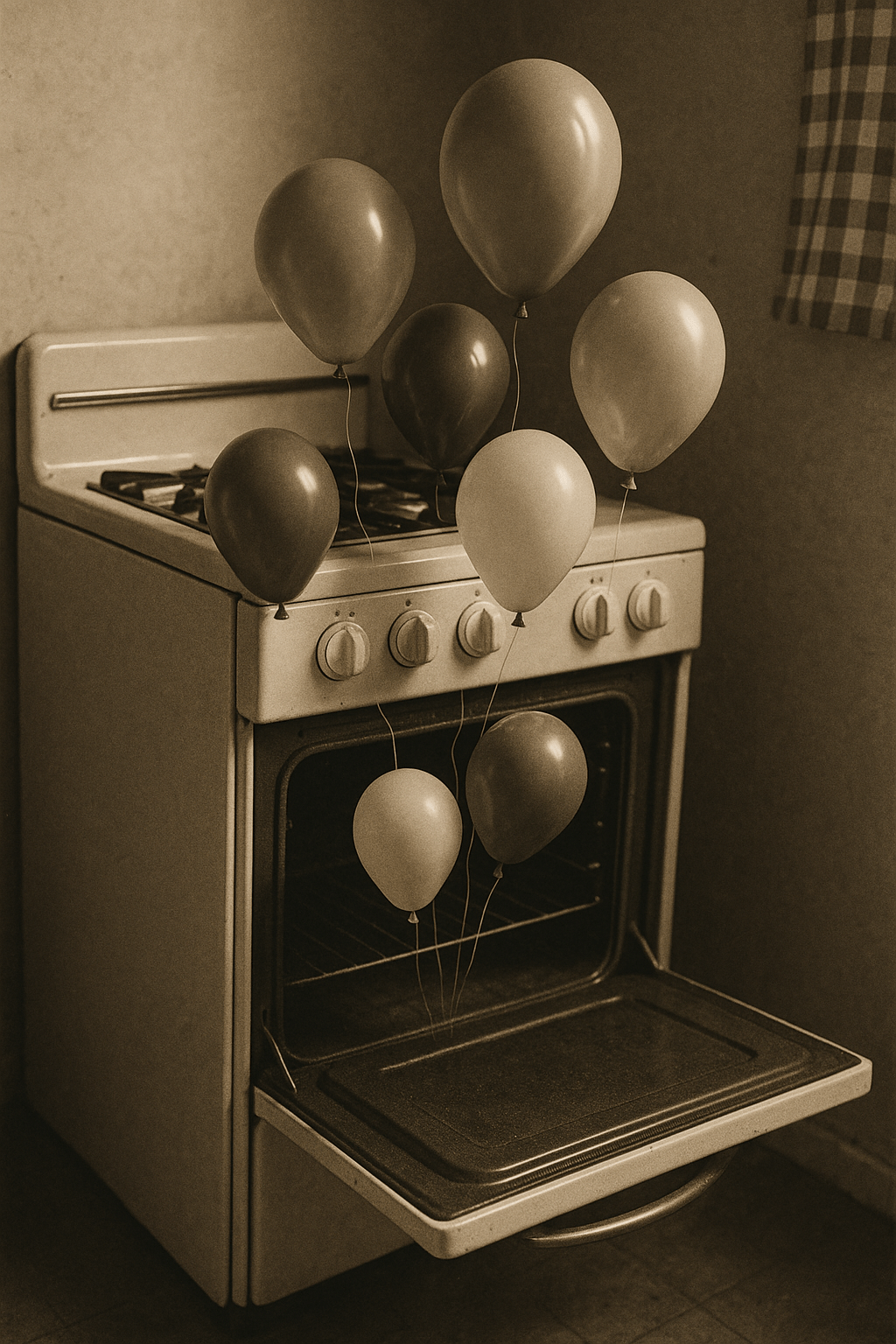

Balloons

Sylvia Plath, February 5 1963

Since Christmas they have lived with us,

Guileless and clear,

Oval soul-animals,

Taking up half the space,

Moving and rubbing on the silk

Invisible air drifts,

Giving a shriek and pop

When attacked, then scooting to rest, barely trembling.

Yellow cathead, blue fish————

Such queer moons we live with

Instead of dead furniture!

Straw mats, white walls

And these traveling

Globes of thin air, red, green,

Delighting

The heart like wishes or free

Peacocks blessing

Old ground with a feather

Beaten in starry metals.

Your small

Brother is making

His balloon squeak like a cat.

Seeming to see

A funny pink world he might eat on the other side of it,

He bites,

Then sits

Back, fat jug

Contemplating a world clear as water.

A red

Shred in his little fist.

The Popping Point: An Exegisis

Originally published December 11 2011

A pin may pop a balloon, but the initial pressure within renders it vulnerable. “Balloons” relates Sylvia Plath’s life to a balloon, as it inflates through a number of contrasting elements in the poem, all leading up to a final pop. This ultimate explosion represents an overarching contrast in the poem between simplicity and complexity. The profuse contrast in “Balloons” parallels the augmenting stress in Plath’s own life, ultimately causing the burst, which represents the final shift from simple to complex.

The first contrast exists between the balloons and Ted Hughes, as the balloons serve as an opposite replacement of Ted. Sylvia’s first Christmas without Ted occurred in 1962, just before she wrote this poem; moreover, the balloons “have lived with [her]” “Since Christmas” (Line 1). “Guileless and clear”, the balloons represent an innocence and genuineness that Sylvia failed to see in Ted after his affair (2). Plath further conveys this message of replacement by saying the balloons are “Taking up half the space, /Moving and rubbing on the silk”, occupying Ted’s half of the bed (4-5). While replacing Ted with these balloons, Plath uses personification to pump life into the balloons from the start. By saying that they “have lived with us”, are “animals”, and “Mov[e] and rub” gives human qualities to these floating globes (1,3,5).

The contrast within the second stanza represents the stress and pressure of Sylvia’s life, as well as its fragility, and parallels her second suicide. Perhaps “Invisible air drifts” refers to the unnoticeable build up of stress in her life, just as air silently fills up a balloon to its popping point (6). Once the stress becomes too much, Sylvia’s reaction is to “Giv[e] a shriek and pop/When attacked” (7,8). Then, “scooting to rest, barely trembling” (8), alludes to her second suicide attempt. There exists a contrast between “rest” and “trembling” that adequately parallels Sylvia’s experience. While her mind was at rest on the sleeping pills, her body was trembling, moaning, and vomiting subconsciously. This reaction reveals Sylvia’s fragility to emotional breakdown, just as pins and teeth threaten balloons. However, this fragility comes with due reason: Just as a air filling a balloon makes it vulnerable to popping, the trauma and emotional distress throughout Plath’s life makes her susceptible to breakdowns.

“Balloons” involves emotions directly, with yellow and blue balloons, while referring to Plath’s resurrection from her second death. The “Yellow cathead” represents her rise from this depression, just as an anchor rises with a cathead (9). The color yellow also provokes an association of happiness with this action. However, just after this is another balloon description, the “blue fish”(9). The use of blue defines this balloon as the sad part, and just as a hooked fish thrashes to be free, Sylvia struggled to stay dead and at peace: free.

In the third stanza begins the shift from simplicity to complexity, opening with the direct contrast of the balloons to other household items. The description of “Queer moons…/Instead of dead furniture!” and “Straw mats, white walls/And these traveling/Globes of thin air, red, green” exposes the disparity between the balloons and the rest of the house (10-14). This contrast deepens the complexity of the house by adding colors and life to the dead, “white”, and bland furnishings. Perhaps this depth-complexity relationship reflects the connection between the emotional depth and intensity of Plath’s poems and the hardship and complications of her life.

The emotional contrast, as the poem shifts from cheerful to tragic in the second half, corresponds with the final simple to complex transformation. At first, in the fourth stanza, the balloons are considered with happy sentiment, “Delighting/The heart like wishes”(15-16). Also, they are compared with “free/Peacocks blessing/Old ground with a feather” (17). This comparison connects back with the description of balloons as “soul-animals” (3). A peacock symbolizes eternal life. So Plath’s association with a free peacock as a soul-animal might represent the contrast between her own sense of eternal life, despite multiple suicide attempts, and her desire for freedom through death. The fact that the feathers are “Beaten in starry metals” signifies the greatness of their “blessing”, as it means divine blacksmiths forged them(18). However, this also presents a weight contrast between “feather” and “metals”, further expanding the balloon. The tone and imagery presented in this stanza convey a positive sentiment towards the balloons, however this comes to an abrupt halt once the child, Sylvia’s young son, gets his hands on one.

A final contrast adds pressure before the balloon pops on the child’s teeth. By “Your small/ Brother…making/ His balloon squeak like a cat”, he is adding pressure to the balloon both literally and figuratively (20-22). Not only is the child squeezing the balloon, weakening the rubber walls, but he also creates contrast within the poem. While the balloon associates with a cat, it actually makes the sound of a mouse.

Now that the balloon has been expanded by contrast throughout the poem, the child pops it, and immediately experiences an influx of complexity. Before, the child “is making/His balloon squeak like a cat. /Seeming to see/ A funny pink world” , frolicking in the simplicity of his imagination (21-24). However, when he tries to eat the pink world, he gets a taste of reality, and finds himself facing a “world clear as water”, as the pink world is nothing but “Invisible air” now, so he “Contemplat[es]” how it came to be (28). This line, however, “Contemplating a world clear as water” has another meaning as well. It reveals the extreme simplicity of the child, as once the balloon pops, he is mystified by a normal phenomenon, and must sit and contemplate something so common to an experienced person. By referring to the child as a “fat jug” (27) Sylvia signifies the baby’s enormous capacity for imagination, with but a little opening into the complexity of real-world thought. Thus, the balloon’s pop widens this opening, and allows an in-pour of complication into the child’s simple life.

The use of “clear” both at the beginning and end of the poem completes the transition into complexity that this balloon has caused. Initially, the balloon, “Guileless and clear”, represented an innocence and lack of deception that made it simple (2). At the beginning of the poem, the balloon has not yet been inflated by all the contrast within the poem, preventing it from popping. But over the course of the poem, contrast expands and weakens the balloon until it bursts. Also in the poem, Plath describes the balloons with various colors, deviating from their initial clarity. However, by the end of the poem, the popped balloon returns to clearness. Irony presents itself in the fact that the popped and intact balloons do not contrast, but rather resemble each other through their clearness. Perhaps this cyclical pattern represents the peace within Sylvia’s own life. Before any contrast and pressure occurs, Sylvia’s life is clear and innocent. During her life, emotional trauma and stress breaks her down until she pops, at which point life becomes clear again, as she frees herself from all of life’s suffering and responsibility.

However, “Balloons” makes one final point that alludes to Plath’s life, and contradicts her belief in freedom after popping, as the child clenches the “red/Shred in his little fist” (29-30). Despite the fact that this child should have been scared by the explosion, he holds on to it in a “fist”, representing his unfazed grip. This description demonstrates the difficulty of fully letting go, even after her life has popped. She acknowledges this in her poem “Tulips” as well, by describing her family photos as “little smiling hooks” (Tulips, 21). The hooks, or grip, of her family keeps her from sinking, but also prevents her from being free of life’s pressure.

“Balloons” effectively compares the pressures of Plath’s life to those inside a balloon, describing a number of contrasts that ultimately lead to the pseudo-liberating pop. Sylvia Plath associates with Confessional poetry, allowing for the making of comparisons between this poem and her life (Sylvia Plath, Poets). Similarly, her poems often couple dark imagery with brighter structural techniques: a contrast that reflects her own personal coupling of pleasure with pain (Sylvia Plath, Poets). This contrast exists within “Balloons” as well, as dark images such as “dead furniture” and the popping of the balloon complement the airy and balloony structure of the poem itself (11). This airy feel derives from the enjambment between lines of “Balloons”. For example, the organization of “Straw mats, white walls/ And these traveling/ Globes of thin air, red, green, /Delighting” separates “Globes” from its adjective “traveling”, as well as the subjects mats and walls from globes (12-15). This poem embodies many facets of Sylvia Plath, from her poetic style to the pressures of her life, as the numerous contrasts lead her to a pop.

Leave a comment